K Hari Kumar, author of Daiva, at its launch in Bengaluru

| Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

BY SMRUTI S

Novelist and screenwriter K Hari Kumar was recently in the city to launch his newest book Daiva. Hari has written eight books and penned screenplays for the Malayalam movie E and the Hindi language web-series Bhram. Almost all of Hari’s books delve into the realms of mythology and folklore, constructing narratives that are psychologically thrilling.

At the launch of Daiva in Bengaluru’s Atta Galatta, Hari said, “An oracle once said whatever you do in life, has to do with the undead and at first, I thought that meant ghosts. But undead does not just refer to ghosts — it is everything that is infinite. Anything that is not dead, is undead. Every spiritual aspect comes under this umbrella.”

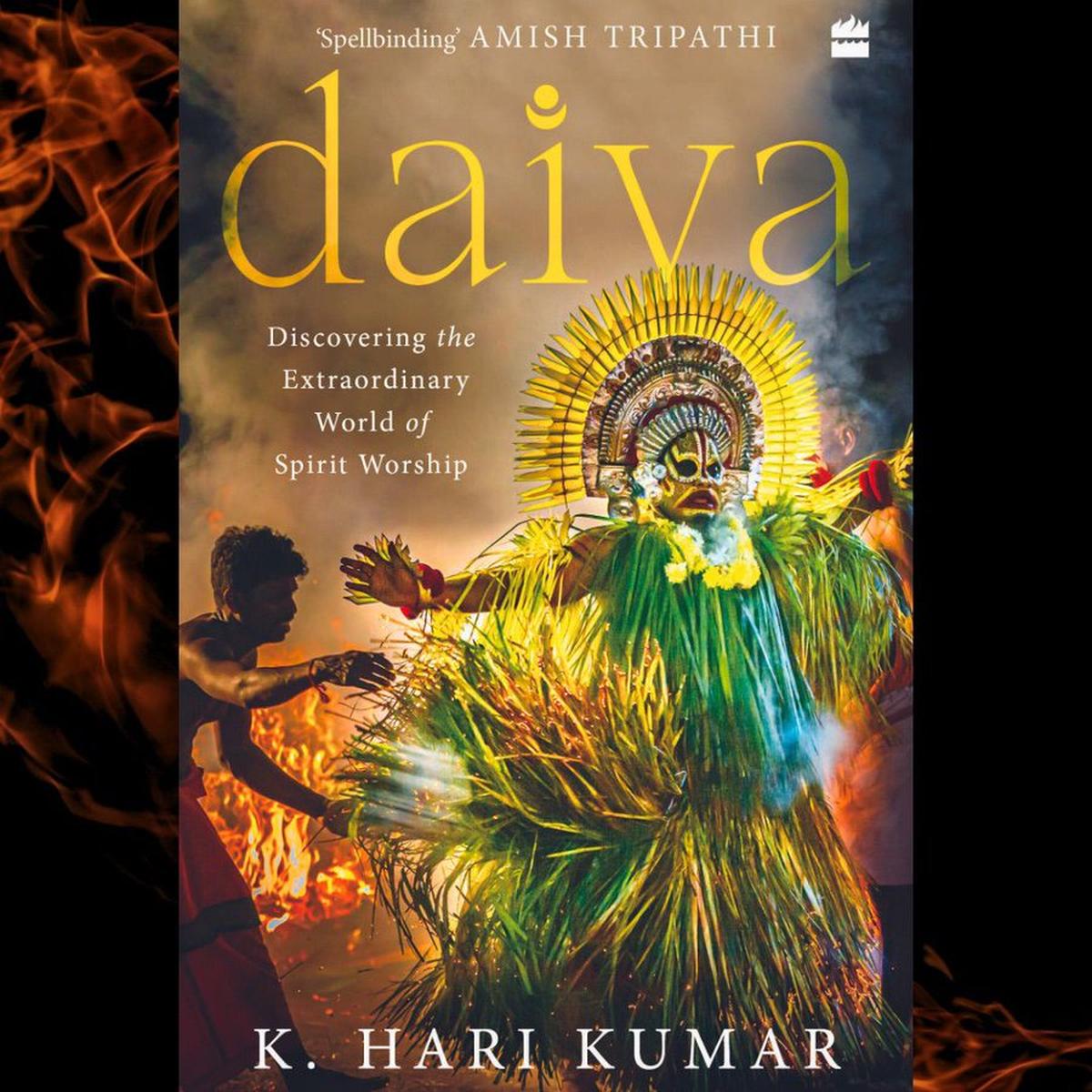

Daiva is a work of non-fiction and deals with the culture of spirit worship or Daivaradhane in the coastal region of Tulunadu. These practices began in a bid to please ancestral gods and protect worshippers from evil. These deities were not just confined to Hindu culture, but came from nature, Matru shaktis (feminine forces), and those who met with a tragic end.

“Daivas aren’t merely myths, especially for Tulu speaking people, it’s a part of their life. They call it Sathyalu or the truth,” he said. The book serves as an introduction to those interested in the world of spirit deities and its practices.

“This is drawn from my personal journey and enquiry into the daivaradhna (spirit worship) of Tulunadu,” said Hari. His ancestors left Tulunadu and with each successive generation relocating elsewhere, a fragment of their culture was lost. “I always wanted to know more about my ancestors and whom they worshipped. That’s how I started my enquiry and that is how my book came into being.”

According to Hari, similar practices of spirit worship are found throughout India and the world. “Daiva is called Thayangullum in Tulu and Theyyam in north Kerala. Certain differences and variations have resulted due to geographic barriers and linguistic evolutions. There are similar trance-based dances in Africa and Tibet as well. Perhaps at a primodial evolutionary level we are all connected somewhere. Those are the existential questions I am seeking while documenting this culture,” he says.

Hari says one of the challenges he faced during his research was the scarcity of English literature on the subject. “There were manuscripts in Kannada and Tulu as well as few written about 140 years ago by Britishers. I began with the manuscripts of AC Bernell. All the stories were based on prarthanas or oral Tulu verses which aren’t written down. I travelled into the Tulu region and got in touch with experts to understand it.”

“If you’re not respectful and are dismissive, you will only see whatever is there on the surface. To people who believe in devaradhane it gives hope, it instils fear. That will only come if you respect it,” he says.

K Hari Kumar, author of Daiva, at its launch in Bengaluru

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Speaking of feminism and spirit worship, Hari said, “Yakshis come from the word yakshini, these are forms of shakti. Similarly, the word dayan is derived from dakini. In Odissa, when there is a property dispute or a fight amongst the menfolk, the women are blamed and called dahini or witch and hanged. Such practices happen even today and activists are fighting against them.”

Hari dropped a few hints about his next book, saying, “From here, I move on to a work of fiction set along the India-Nepal border about a female deity who has been wrongly branded as a witch.”

A lot of rework had been done to draft a screenplay for Bhram that was based on his book, The Other Side of Her. Though the story remained the same, the cultural premises had to be revised.

Hari says when one writes for OTT, they are at mercy of the creative team. “Though I had envisioned the story in Kerala, the producers were not convinced about an actor from the South playing the lead. We had no option but to create a fictitious tribe and change the protagonist to a North Indian.”